Religious Liberty Commission Yearly Report 2021

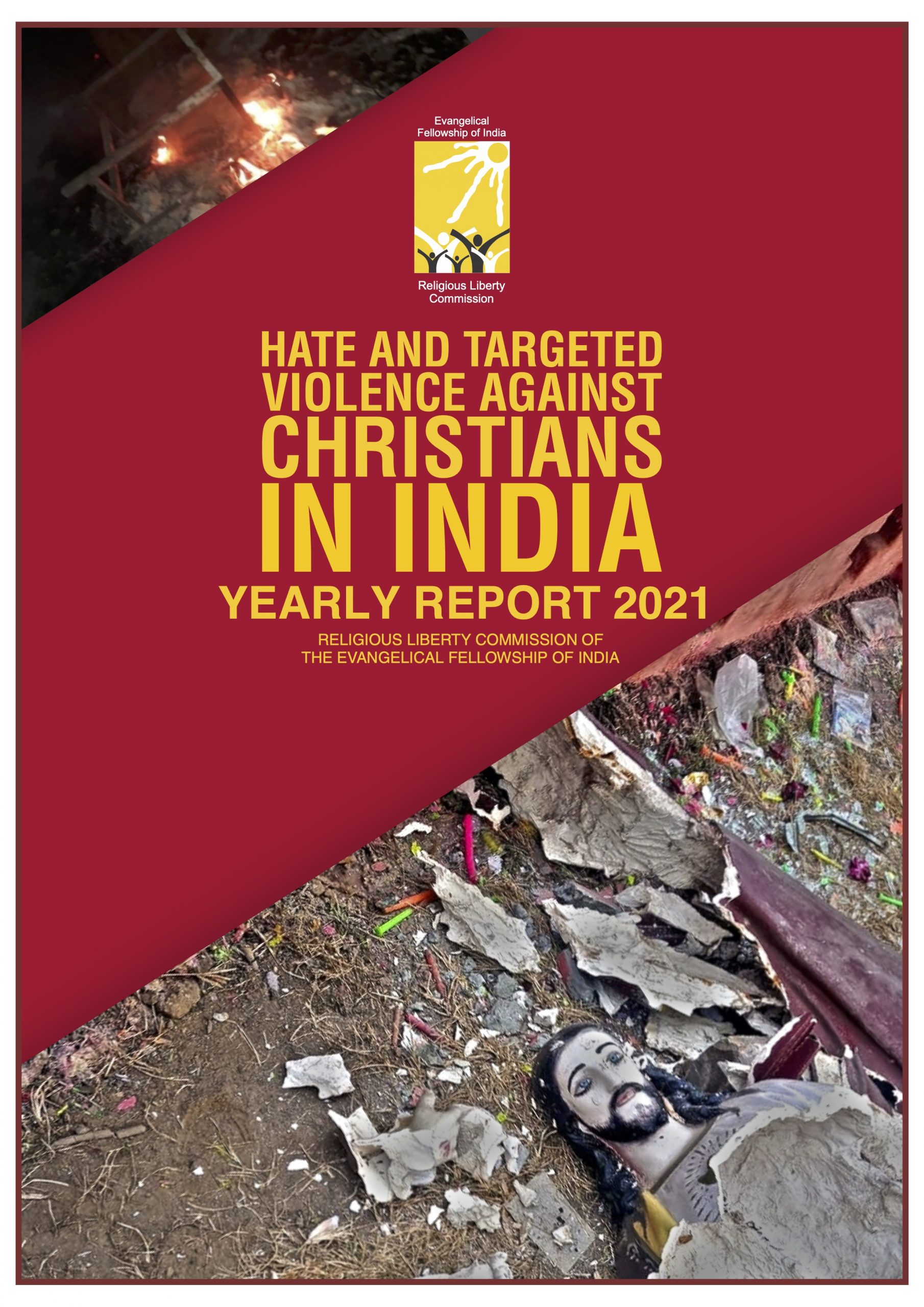

Soon after midnight on 25 December in the old military town of Ambala Cantonment in Haryana, two miscreants entered the Holy Redeemer Catholic Church, a landmark first built in 1848 and rebuilt in 1905. They shattered a statue of Jesus Christ at the entrance gate, throwing the head on the lawns, and damaged the lights they could reach. In a final act of hate and contempt, they urinated at the doors of the historic building that has stood through wars and the partition of India.

This terrible act of vandalism and desecration was one of sixteen acts of violence against the Christian church and community in India on Christmas day. By the time the year 2021 ended six days later, the Religious Liberty Commission of the Evangelical Fellowship of India had recorded 505 individual incidents of violence including three murders, across India. Some other agencies that document violence totaled a larger figure.

No denomination whether organized or a lonely independent worshipping family or neighborhood group, none has been spared targeted violence and intense, chilling hate, the worst seen since the general election campaign of 2014. The year 2021 saw calls for genocide and threats of mass violence made from public platforms, and important political and religious figures on the stage.

Uttar Pradesh, which was to go to the polls to elect a legislative assembly, topped the 2021 list with a record 130 cases, with Chhattisgarh at 75, neighboring Madhya Pradesh with 66 and Karnataka in South India at 48. West Bengal, Himachal Pradesh and Jammu and Kashmir, now a Union Territory, documented one case each. The North-eastern states as well as Kerala and Goa on the west coast did not record any case. All of them have sizable populations of Christians.

This was perhaps the third most violent Christmas the community has faced in India. On Christmas eve of 1998, 36 rural log churches were burnt and destroyed in the Dangs forested district of the state of Gujarat. The incidents were dubbed a “laboratory for right wing religious and nationalist fanatics.” On Christmas eve of 2007, another forest district, this time Kandhamal in the state of Orissa [now called Odisha] became the laboratory. Villages houses, small prayer halls, large churches, and institutions were burnt, and people forced to flee for their lives into the forest. The violence was repeated a few months later. More than 100 were killed, many women, including a Catholic Nun raped, and close to 400 Churches and institutions destroyed. The Orissa government had identified the attackers as belonging to an arm of the Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh which had launched a massive hate campaign targeting the Christian community.

An analysis of the aggregated data shows that Christians were most vulnerable to attacks in the second half of the year, particularly in the months from August to December, the Christmas season. While October topped the list with 74 incidents followed by December with 64 incidents, August and September saw 52 and 50 cases respectively. The hot summer months of May and June were the most pacific (13 and 26 cases).

While three persons were murdered, in terms of other crimes enunciated in the Indian Penal Code, Coercion, Intimidation, Threats of violence and harassment of Christians was the most “common” crime with 137 cases, with arrest by police on fabricated cases close behind sat 81 cases. Of these, 17 persons were jailed by the police. Physical violence[1] took place in 84 cases, while in 7 cases attacks on women were seen. Worship in churches of various sizes was interrupted or forced to stop in 66 incidents and 5 churches were destroyed. Critically for the communities in tribal and other rural areas, there were recorded 36 cases of social boycott[2] and ostracization, and 7 cases of forced conversion to Hinduism.

The real figures may be much more – even without the additional hardship and difficulties faced in a period when India was raged by the second wave of Covid. The nation was trying to cope with unprecedented disaster — which saw patients gasping for oxygen, which was in short supply in hospitals, others dying on the way to hospital, and bodies being thrown into the Ganges and other rivers as cremation grounds were overwhelmed by the death count. It had little time to investigate violence on a small minority community. Covid did not prevent the perpetrators of such crimes.

Even in normal times, it is difficult to document all incidents of persecution. Much of the crime takes place away from the big stages, often in large villages and tribal areas deep in forests. In many cases, victims are too scared to report persecution. They face coercion and threats from the local vigilante and political groups, and their thugs and musclemen, who are often armed with guns and swords. When the Christian who has been beaten up, assaulted, or threatened that he or she would be killed if they approached the police, do go to a police station to file a complaint, they often find that the police is hesitant to record the crime or in some instances, are complicit.

Another avenue for targeted hate was added with the “surveys” of Christian places of worship in the state of Karnataka which preceded the passing of an anti-conversion law by the legislature. Karnataka will be the tenth state to have such a law that all but criminalizes interfaith marriages and exposes believers in Christ to police and social harassment even before they convert or are baptized. Long jail terms and heavy fines are listed for violations, including “fraud” or “force’ if used by the pastor. Wherever the Anti-Conversion law, ironically officially called Freedom of Religion Act, was passed, it became a justification for the persecution of the minorities and other marginalized identities. The attacks on the minorities grew sharply in recent years since this law was tweaked and used as a weapon targeting the dignity of Christians and Muslims.

The Indian constitution provides six broader fundamental rights. Everyone is equal and has equal rights and freedom without discrimination before the law (Art 14-18) & (Art 19-22). The State provides freedom of conscience and right to profess, practice and propagate religion (Art 25-28) as well as cultural & educational rights for the religious minorities (Art 29-30). It is right to equality, freedom, and non-discrimination for every citizen.

The anti-conversion laws violate international covenants and instruments where India is a signatory. Articles 1, 18 & 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), Articles 18 &19 of International Covenants on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the Articles 2 & 3 of UN Declaration on Elimination of All Forms of Intolerance and of Discrimination Based on Religion or Belief spell this out clearly and categorically.

You can download the report by clicking THIS link.

[1] In this analysis, “Physical violence” is recorded when the situation has escalated beyond threat and harassment to cause, or result in, pain and/or physical injury to the victim on account of his or her Christian faith during an altercation. The victims may not have necessarily been hospitalized.

[2] Social Boycott is an act of persistently avoiding a Christian/s by other members of the society/village because they practice and profess Christian faith. It is the collective refusal to engage with Christian/s in normal social and commercial relations.